Ophthalmology’s journey with anti-VEGF injections for neovascular age-related macular degeneration is an embodiment of the old saw, “The devil’s in the details.” At first blush, the anti-VEGF mainstays—bevacizumab, ranibizumab and aflibercept—are revolutionary, effective treatments for the disease. Once you start to implement them, however, you’ve got a raft of new issues to deal with: You have to maximize disease control, improve vision and maintain a stable macula by finding a treatment interval and drug with sufficient durability that also accounts for the real-world obstacles patients face coming to the clinic. Fortunately, there are several newly available nAMD treatment options that aim to contend with some of these hurdles: a bi-specific agent; a ranibizumab-eluting implant; and ophthalmology’s first biosimilar.

Here, retina specialists share how they meet these treatment goals, describe how they overcome these obstacles to care, and detail some of the newest anti-VEGF agents in the armamentarium.

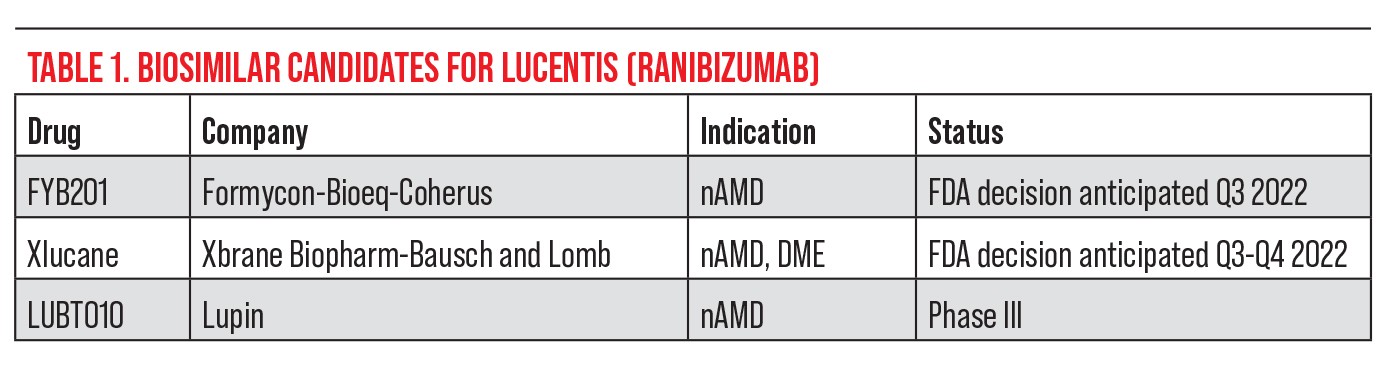

Finding an Interval

“When I started my career, there weren’t many great treatments available for nAMD,” says Ian C. Han, MD, an associate professor at the Institute for Vision Research, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics. “Now there are many different ways to preserve vision.

“I often tell patients that the best-case scenario is if they come in for their routine retinal exam and we find signs of early nAMD that the patient doesn’t even notice,” he continues. “It’s a bit interesting trying to tell a patient they need to embark on treatment when they still may be 20/20 and have no symptoms, but the earlier you begin treatment, the better you’re off downstream.”

Treat and extend is currently the main protocol used for nAMD treatment. “We have more data now on the consequences of central subfield thickness fluctuation, so I think physicians are realizing they can have better disease control and better outcomes with treat and extend instead of pro re nata,” says Arshad M. Khanani, MD, of Sierra Eye Associates in Reno. “Fluctuations in CST lead to worse outcomes, so it’s important to have a treatment protocol that keeps the retina dry and stable instead of allowing these fluctuations, as was the case with PRN.”

“PRN was never a great idea,” agrees David M. Brown, MD, of Retina Consultants of Texas. “I call it ‘progressive retinal neglect.’ It never made sense to wait for a hemorrhage to recur before treating. However, treat and extend is a misnomer of sorts. We all do fixed dosing at some interval; treat and extend is just a way of figuring out what an individual patient’s fixed interval will be.

“Typically, we give two or three loading doses, and if the patient doesn’t have any active disease—i.e., no fluid or hemorrhage on OCT—then we extend it a few weeks. Say at six weeks, if they’re dry, we might give the patient another shot and try eight weeks. Eventually you extend until you get fluid and then back off to the interval at which they stay dry. This approach gets us to a personalized fixed dosing interval as quickly as possible.”

This is the main benefit of treat and extend, according to experts. Rather than lumping all patients into one basket with PRN or monthly injections, this protocol tailors the treatment to optimize disease control. Additionally, “We know that many patients don’t like to come to the clinic every month, or they aren’t able to for a variety of reasons, and this leads to poor disease control and vision loss,” says Dr. Khanani. “Patients need to be compliant with whatever treatment protocol they’re using, but with fewer injections, we have better overall compliance because of the decreased treatment burden.”

Some evidence has suggested that more frequent dosing may yield slightly better visual outcomes, but a Cochrane review found the difference to be clinically negligible.1 The review found that patients receiving monthly injections had slightly better vision at one year compared with those receiving as-needed (average: seven) or modified as-needed/treat-and-extend injections (average: nine). Endophthalmitis was thought to be more common with monthly injections.

|

Agent Selection

Which anti-VEGF agent is best suited for which patient? There’s no clear answer, experts say, as aflibercept, ranibizumab and bevacizumab are all effective at slowing disease progression. “It’s a tough decision and there’s no perfect answer,” says Luis J. Haddock, MD, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Miami, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. “Maybe in the future, we’ll be able to predict whether a certain patient will respond best to a specific drug based on OCT findings. Prior studies have shown that all of the anti-VEGF agents are effective in treating the disease, some perhaps more so than others. It comes down to clinical findings, pathology and how often the patient can come back to the clinic. If a patient comes to me already on a certain medication and they’re doing well, I may not switch them. With new patients, I often try bevacizumab first and monitor the effect. Most patients respond well.”

“I and most of my partners at the University of Iowa generally start with bevacizumab,” says Dr. Han. “Though it’s off-label, it has a long track record, is the least expensive, has a good safety profile and works well for the majority of patients. Most anti-VEGF treatments will work well for most people. Other practices may decide to start with a different medication, but the upshot is that most work well regardless of what you pay.”

“Choice of agent sometimes depends on a patient’s insurance and socio-economic status,” Dr. Brown points out. “Most insurance companies now have a few step edits, where they want us to start with bevacizumab, which is our weakest agent. It’s made by compounding pharmacies, so it doesn’t have the same consistency as the branded agents, but if a patient is doing well on bevacizumab, we often stay with it.”

If coverage isn’t an issue, Dr. Khanani says he starts patients on faricimab because it has good efficacy and durability. He also points out that patient education is important when discussing AMD treatment. “We make sure they understand that nAMD is a lifetime disease with no cure, though we have a treatment,” he says. “Then we review the currently available agents and what’s approved by their insurance. We make sure they understand that no agent will obviate the need for injections. It’s more along the lines of which agent will maximize treatment intervals. In that case, the patients need to understand that they can’t miss their visits—they really need to come for every injection, otherwise they could end up with vision loss. Patients are a big part of decision-making, and together we decide how they want to proceed. But of course, as the physician, it’s my goal to give my patients a durable agent so we can decrease their treatment burden.”

As you know, brolucizumab is no longer considered a first-line treatment for nAMD due to the intraocular inflammation events seen in some patients. Dr. Han says brolucizumab has been an instructive medication for the field. “Brolucizumab and faricimab are the newest drugs since aflibercept, which still seems new but was actually FDA-approved more than a decade ago in 2011,” he says. “This highlights the advantages of innovation—we can potentially have a drug that works better for some patients, especially those who have had a limited response to other available drugs on the market. Many drugs coming down the pipeline are also targeting other molecules and pathways associated with blood vessel growth to have greater effect or durability of effect.

“That said, I’m very hesitant to use brolucizumab and have only used it rarely,” he continues. “The possibility of severe inflammation resulting in vision loss and retinal vasculitis isn’t a trivial one to consider. Unfortunately, drugs can make it to market even after rigorous clinical trials and still have safety signals turn up after approval. You always have to be a bit cautious whenever a new drug comes out because the real world is different from a clinical trial.

“There are some patients who may have had frequent injections and tried every available drug and can be switched over to brolucizumab with a more efficacious response in terms of visual acuity or exudation,” he says. “Brolucizumab is a powerful drug, and it came to market because it had an advantage over the standard of care. Still, the risk-benefit ratio is difficult to take, especially compared to the long safety track record of the existing drugs and the severity of the complications.”

Dr. Haddock says he unfortunately experienced some of the inflammation and vasculitis-related adverse events described in the literature. “I didn’t feel comfortable continuing to use that medication when we have other agents that perhaps have a similar overall efficacy and haven’t been shown to have those effects,” he says. “In general, the medication has shown efficacy and potency and works in the disease—I had patients in whom it worked very well—but with those concerns in mind, my personal preference is to not use it.”

Dr. Khanani considers brolucizumab a fourth-line agent for patients who have persistent disease with vision loss. “Patients who are on aflibercept with poor response will now likely switch to faricimab, and if they still don’t respond, then brolucizumab would be a fourth-line option,” he says.

If your patient is receiving brolucizumab injections, experts say continuous monitoring is crucial, though the warning signs would be similar to any other anti-VEGF agent (e.g., signs of post-injection inflammation, photophobia, decreased vision). “Brolucizumab is really powerful in terms of disease control, so if the patient is willing to take the risk, we monitor them closely and instruct them to call us right away if any new symptoms occur,” Dr. Khanani says. “Every time they come to the clinic, we perform a dilated eye exam and look for signs of inflammation. If they have any signs of inflammation, I stop using brolucizumab there. That’s what prevents a bad episode down the road.”

He says the results of a real-world safety-outcomes study published in JAMA Ophthalmology that he was a part of found that the main risk factors with brolucizumab were a history of retinal artery occlusion and a history of inflammation.2 The cohort study included nAMD patients in the IRIS Registry and Komodo Healthcare Map databases; it reported an intraocular inflammation and/or retinal vascular occlusion incidence rate of 2.4 percent.

Patients who had IOI and/or RO in the 12 months before receiving their first brolucizumab injection had the highest observed risk rate for IOI and/or RO in the early months after their first injection. “We would exclude these patients,” Dr. Khanani says. “There’s also some data suggesting that inflammation is more common in females.” The estimated incidence rate in women compared with men was 2.9 and 3 percent vs. 1.3 and 1.4 percent in the IRIS and Komodo groups, respectively. (The study authors pointed out that the identified risk factors can’t be used as predictors of IOI and/or RO events and their causality with brolucizumab can’t be assessed using this study.)

|

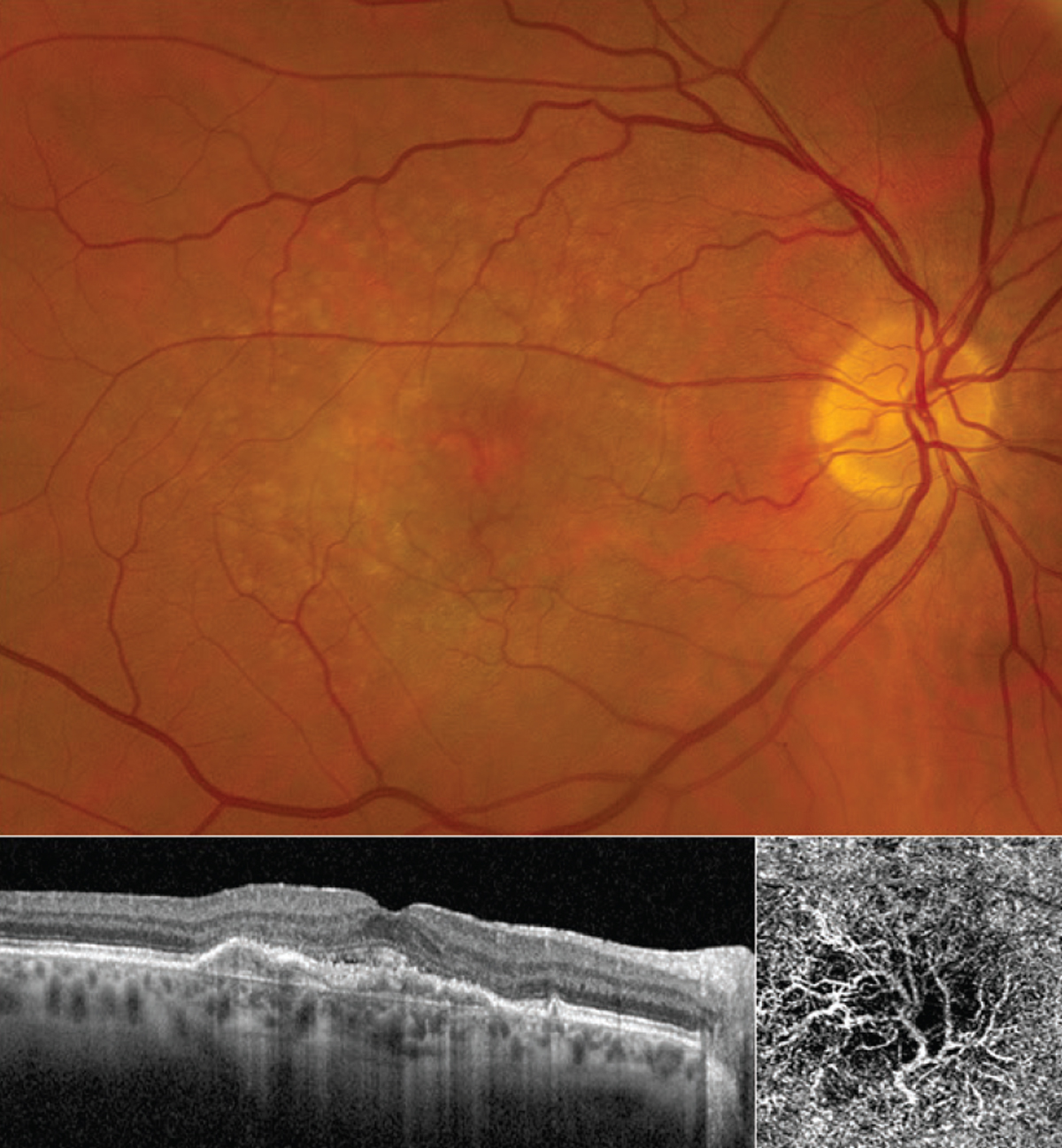

| Figure 1. An otherwise healthy woman in her 60s first noted blurry vision and distortion in her right eye more than a year ago and was diagnosed with nAMD. The fundus photo shows numerous drusen characteristic of AMD absent of any subretinal blood. (The CNV is not obvious in the photo.) OCT line scan (bottom left) shows elevation of the retinal pigment epithelium and thin overlying subretinal fluid, consistent with a subfoveal (“type 1”) CNV. OCT angiography (3 x 3-mm fovea-centered “ORCC” outer retinal to choriocapillaris slab) shows a prominent CNV with mature-appearing vasculature and surrounding choriocapillaris loss. This patient has maintained excellent (20/25) vision with anti-VEGF therapy on a treat-and-extend regimen. Photo: Ian C. Han, MD. |

Imaging for Retreatment

When deciding when to retreat an nAMD patient, retina specialists rely on optical coherence tomography as their primary imaging modality. In addition to OCT findings such as subretinal fluid, subretinal hyperreflective material, atrophic changes and choroidal findings, vision changes and disease resistance factor into the treatment decision.

“When deciding when to retreat, I typically look at subretinal and intraretinal fluid and the size of the retinal pigment epithelium and try to take everything into consideration,” says Dr. Haddock. “I also use OCTA to better visualize the size of the choroidal neovascularization and where it’s located to determine which patients can tolerate a little more fluid.”

Dr. Haddock also considers the patient history and whether they’ve previously undergone a treat-and-extend regimen. “It’s important to know their parameters and what they can tolerate,” he explains. “Patients with a small area of subretinal fluid, even if it’s central, may have stable vision and no new bleeding, and they may be okay to remain at a certain interval rather than shortening it. I would tolerate a little bit of subretinal fluid rather than intraretinal fluid because there’s enough evidence to suggest to that intraretinal fluid may predict worse overall outcomes.”

“I’ll often couple OCT with OCTA to follow the abnormal vascular complex when deciding when to retreat,” Dr. Han says. “Our goal is to resolve any pathologic changes we see, such as intraretinal and subretinal fluid. We treat until the fluid goes away or stabilizes.”

While OCTA isn’t the standard of care for monitoring nAMD, it’s a valuable technology complementary to the existing imaging modalities, proponents say. Dr. Han says he likes to be able to correlate structural and vascular features in a three-dimensional fashion through OCTA. In fact, his current research focuses on multimodal imaging for studying the physiologic mechanisms of retinal disease, including abnormal blood vessel changes, which he says aren’t always so straightforward.

“There are some gray zones concerning these blood vessels,” Dr. Han explains. “There’s evidence that even persistent subretinal fluid might not be a bad thing. Patients with persistent subretinal fluid might actually have very little choroidal vasculature under the fovea where it counts most for central vision, and the choroidal neovascular net that we deem pathologic may actually be a secondary response to tissue thinning or vascular loss (Figure 1). We might not want complete regression of the choroidal neovascularization since it may be supplying nutrients to the fovea. The persistence of that fluid may be representative of the fluid clearance or transition as opposed to actual activity of the blood vessels. Many of these patients can maintain very good vision, even with some fluid on OCT. Ultimately, treatment depends on a lot of different factors for individual patients.”

OCT should be performed at every visit, or monthly, until the fluid has dried, says Jay Chhablani, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh Eye Center. “Many physicians don’t do an OCT during the loading doses or the first three months, but I like to get an OCT every visit just to better understand the response. Looking at the initial response helps you when you go back to look at later changes. So, I would say get an OCT every month until you decide they’re dry and extend it to two or three months follow-up.”

|

To Switch or Not to Switch?

If your patient seems to be a non-responder, first rule out any other disease that may have been missed in the beginning of the treatment, says Dr. Chhablani. “To rule out a retinal pigment epithelial rip, we use fundus autofluorescence,” he says. “This modality won’t help you every time you need to redefine the treatment interval, but it can help you differentiate nAMD from other causes of neovascularization.

“We don’t ask for fluorescein angiography much since it’s an invasive test,” he continues, “but if I suspect my patient isn’t responding well due to a polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, I’ll definitely ask for an indocyanine green angiography along with fluorescein angiography, and review all of the patient’s pictures to see if there’s any other associated disease. If the patient has PCV, I’d offer a combination treatment of photodynamic therapy along with anti-VEGF.

“Not many U.S. physicians get ICGA done since they feel PCV isn’t very common here, but patients do get it,” he adds. “ICGA is something we want to push forward in the next generation of residents and fellows so we can better understand the prevalence of PCV in a white population.”

If your nAMD patient has persistent fluid despite monthly therapy or cannot be extended from a monthly regimen (i.e., if fluid recurs after extending), it’s time to proceed up the pathway to a stronger agent, says Dr. Brown. “Most of our agents all work by blocking VEGF,” he says. “Aflibercept has more anti-VEGF blockade than ranibizumab, which has more anti-VEGF blockade than bevacizumab. Faricimab, which was recently approved, has even more anti-VEGF blockade and also blocks Ang2, which may be particularly important in vascular diseases such as diabetes and retinal vein occlusion.”

Additional switching considerations may include where in the retina the patient’s disease first presented, the amount of fibrosis, fluid and disease activity, and the patient’s response to the prior medication, adds Dr. Haddock. “If I see a patient having a slow response, I may give them more time,” he says. “If they have no response, I’m more likely to switch agents. Typically, after three injections, I have a good idea of who’s a responder, who’s responding at the rate I anticipated and who has potential of responding with another medication. After three or four injections, I’d make the decision taking those factors into consideration.”

“If your patient can’t afford to switch to a different agent or doesn’t have access to the newer medications, then a double dose of aflibercept works well, or more frequent anti-VEGF,” says Dr. Chhablani. “You can also combine bi-weekly injections, e.g., aflibercept and alternate with bevacizumab every 14 days.”

Some recent studies using simulated switch protocols have suggested that switching agents may not necessarily give patients better outcomes. Dr. Chhablani points out, however, that there are a lot of factors we’re still unable to evaluate in studies, and simulation studies can’t match those. The sub-analyses in question are those of the HARBOR trial,3 CATT and DRCR.net trials4 and the ARIES trial.5 These studies noted that without a true randomized control group continuing the original treatment, it’s not possible to know whether any improvement is due to the new treatment or not. They identified trial patients who would otherwise be considered for switching drugs in the first several months of treatment and followed them as they continued their original treatment. All three trials, which had company sponsorship, reported visual gains and some improvement in retinal thickness.

“What kind of imaging findings were being treated? How did the patients respond to treatment? These are very important questions,” Dr. Chhablani says. “I have seen in dermatology literature that if a patient becomes resistant to or a non-responder to a certain drug, they give the patient a holiday period and then reintroduce the same drug and the patient responds again. So, some of these things may still be possible, but I’d say that when treating your individual patients, you should certainly consider switching drugs.”

|

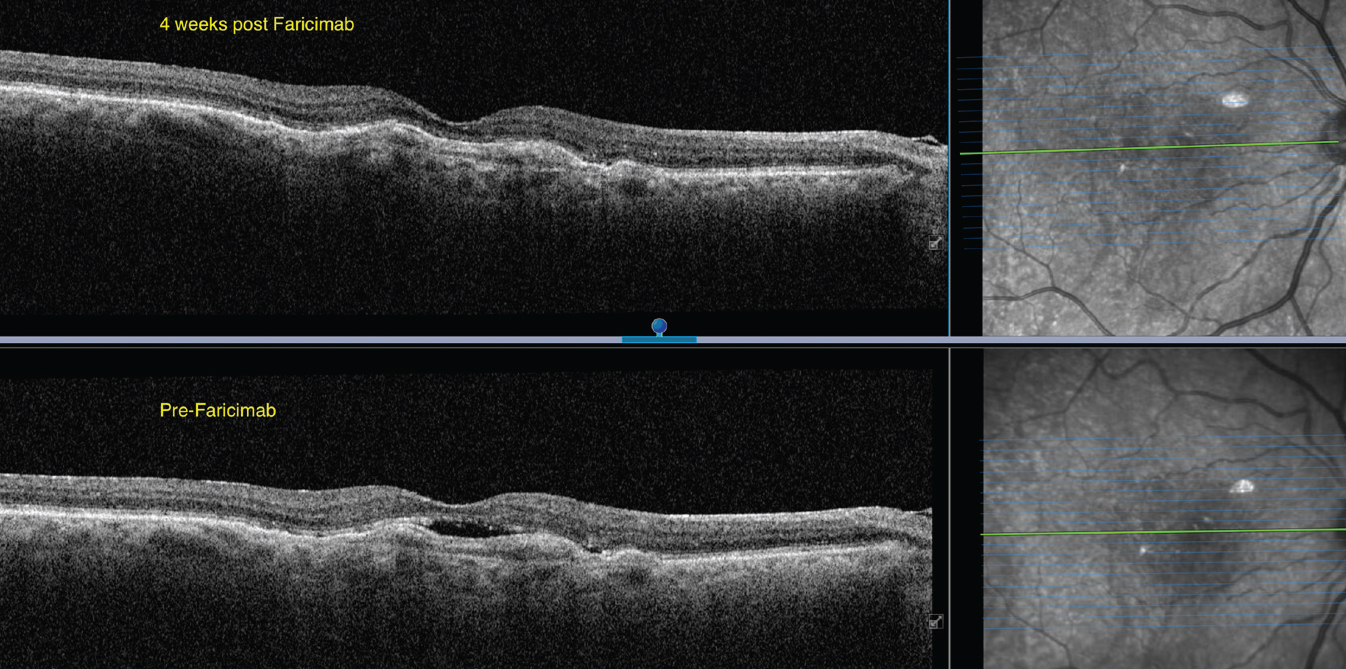

| Figure 2. A 74-year-old female on chronic anti-VEGF treatment for nAMD of the right eye without fluid resolution. OCTA shows a subfoveal choroidal neovascular membrane. Fluid resolution and improvement on OCT were noted four weeks after injection of faricimab. VA improved from 20/100 to 20/80. |

Powerful Newcomers

It’s an exciting time to be in retina with several new treatments available and in the pipeline, retina specialists say. Here are the three most recent arrivals to the retinal disease armamentarium:

• Vabysmo. Faricimab-svoa (Vabysmo, Genentech) is a bi-specific antibody that was approved for nAMD and DME treatment in May. It binds both VEGF-A and angiopoietin2. Faricimab is given in four loading doses followed by maintenance dosing every two, three or four months for nAMD. In the Phase III trials, intraocular inflammation rates were consistent with aflibercept-treated eyes.

“Based on TENAYA and LUCERNE, we found that a subset of patients can last 16 weeks on faricimab, and eight out of 10 patients can last 12 weeks or longer,” says Dr. Khanani, who was one of the clinical investigators. “There are patients who may need more frequent treatment, and they’ll be able to receive faricimab frequently to control their disease.

“Though there are great agents available, we have an unmet need for durability,” Dr. Khanani continues. “Patients don’t gain vision the way they should in the real world because of the treatment burdens, so having a dual mechanism of action that goes after a well-established target and another pathway is exciting. We’re not increasing the burden of injection and we’re maximizing treatment durability this way.”

Dr. Khanani is also part of the AVONELLE-X extension study, which is assessing the outcomes with faricimab for all patients, in particular those switching from aflibercept. “We’re looking for any safety signals that patients are responding better versus which characteristics indicate a patient may need more treatment,” he says. “We’re learning a lot about the drug.”

Dr. Khanani presented faricimab’s two-year data at the ASRS Meeting this year. The data show that almost 80 percent of patients receiving faricimab were able to be treated every three months or longer; and more than 60 percent of patients were able to be treated at four-month intervals, which represented a more than 15-percent increase since the primary one-year analysis. These patients also had vision gains comparable to patients receiving aflibercept every two months. Faricimab patients received an average of 10 injections over two years and aflibercept patients received an average of 15 injections over the same time period. The study found no new safety signals.

Dr. Haddock began using faricimab a few months ago and says the early results have been encouraging (Figure 2). “I’m still in the stage of seeing how my patients are responding and figuring out what role faricimab will play in their overall management, but there have been good responses so far,” he says. “I haven’t seen any episodes or events that aren’t typical of other anti-VEGF agents.”

“I think it’ll be interesting to see how other physicians use faricimab,” says Dr. Han. “The Phase III trials were encouraging. I’d say I’m a cautious adopter of new treatments. The trial was set up as a non-inferiority comparison to aflibercept, but this was based on a particular protocol in a particular patient composition, so how that plays out in the real world remains to be seen. We haven’t used it yet here at the University of Iowa, but we’re in the process of getting a hospital formulary and insurance coverage for it.”

Dr. Han says he’s excited the field has begun exploring pathways beyond VEGF. “A bi-specific drug is cool to describe, but it also acknowledges that vascular growth, development and stabilization are dynamic and complex processes,” he says. “Angiogenesis, which involves not only new blood vessel growth but also blood vessel remodeling and stabilization is important for life because blood goes everywhere. Life is about balance—growing new blood vessels and then stabilizing them. The challenge presented by neovascularization isn’t necessarily that blood vessels are growing in response to something, which is the body’s typical response to lack of blood flow or injury. That in and of itself isn’t bad, but these blood vessels can grow in the wrong position or be poorly constructed at first, and that’s really a secondary complication or consequence of neovascularization, if you will. Other pathways contribute to this growth, development and stabilization that aren’t currently being addressed with anti-VEGF therapy, which is essentially monotherapy for one molecule. To target more than one molecule to return the body to balance is exciting.”

• Susvimo. Formerly known as the Port Delivery System with ranibizumab, Susvimo (Genentech) provides continuous delivery of the drug. It’s indicated for patients who’ve previously responded to at least two intravitreal injections of an anti-VEGF agent. “We’re always looking for new ways to deliver drugs, including existing drugs like ranibizumab, and to increase their durability and effect,” says Dr. Han. “Social determinants of health, unfortunately, impact patients’ treatment. While they aren’t medical, they still must factor into medical decision-making. A longer delivery system is an important innovation for nAMD.”

Dr. Khanani’s practice was the first to implant the device in a hospital setting. “The implant is a surgical device that helps to control disease and decrease the treatment burden to every six months,” he explains. “Because it’s a surgery, there are risks associated with it, so the first thing we need to do is ensure the surgery is done properly so we don’t end up with complications, and patients need to be monitored. Any adverse events must be treated aggressively and quickly. It’s not a first-line treatment option, but it is a good option for a subset of patients who really don’t like injections or need frequent injections.”

When monitoring patients who have a ranibizumab implant, it’s important to watch them closely in the postop period and ensure the surgical site heals well so there’s no conjunctival retraction or erosion, experts say. Once the site has healed, follow-ups can be extended, but Dr. Khanani emphasizes the importance of educating patients about reporting any issues promptly.

How Much Does Susvimo Cost Compared with Ranibizumab Injections? A cost-analysis study published in JAMA Ophthalmology in June reported that Susvimo with one refill cost more than intravitreal ranibizumab or aflibercept injections if the patient needed less than or equal to approximately 11 or 10 injections, respectively, within the first year.8 If fewer than 4.4 and 3.8 injections are needed per refill, then intravitreal ranibizumab or aflibercept costs less. —CK |

“If a patient has a conjunctival issue and calls us right away, we can repair it, but if they don’t come in right away, they could end up with a complication such as endophthalmitis,” he says. “We monitor them one day, one week and one month after. Once they hit six months and their disease is well controlled and they don’t need any supplemental injections, it’s reasonable to follow those patients every six months just for a refill or exchange procedure.”

At Dr. Han’s midwestern practice, many of his patients drive a good distance to come to the clinic. “We have some limitations with travel distance for many patients who need injections, so many are in favor of an option that lasts longer,” he notes. “But many are perfectly happy to stick with a treatment they know and trust rather than try something new.”

“I’ve discussed the implant with some of my patients and they seem to have more fear of surgery than injections,” says Dr. Haddock. “I think a lot will depend on the physicians—how comfortable we feel with the procedure and how strongly encouraged we are by the results in order to present it to our patients as an option. I don’t think this will be my primary choice for most people, but those who have difficulty coming in for injections are probably the ideal candidates right now. There’s the possibility of a slight increase in infection rates over the lifetime of the implant compared with injections. I’m still seeing where it fits into my armamentarium.”

Dr. Haddock hasn’t used the ranibizumab implant yet, but he’s in the process of getting trained. “Genentech has online modules and also provides in-house training,” he says. “So far, it’s a very nice setup. I think they knew from the beginning that in order to introduce a surgical procedure they really needed to spend time creating good training. There are good surgical training modules and people to teach us the techniques.”

Dr. Brown notes that the implant’s warning label, saying that up to 2 percent of patients get endophthalmitis, or one out of 50, has limited its market access. “Additionally, its current drug eluting levels often don’t cover those who need the most frequent injections,” he says. “In other words, the patients who really want to have this implant are the ones who have to have an injection every month, but this probably doesn’t provide enough anti-VEGF blockade to accommodate those patients.”

Dr. Brown implanted about 35 of the devices in the clinical trial. “The patients who need only one refill every six months are very happy,” he says. “They absolutely love it. And again, the ones who aren’t happy are those who were getting an injection every month and then, after undergoing a surgery for the implant, find the implant still isn’t enough and they have to continue getting injections.”

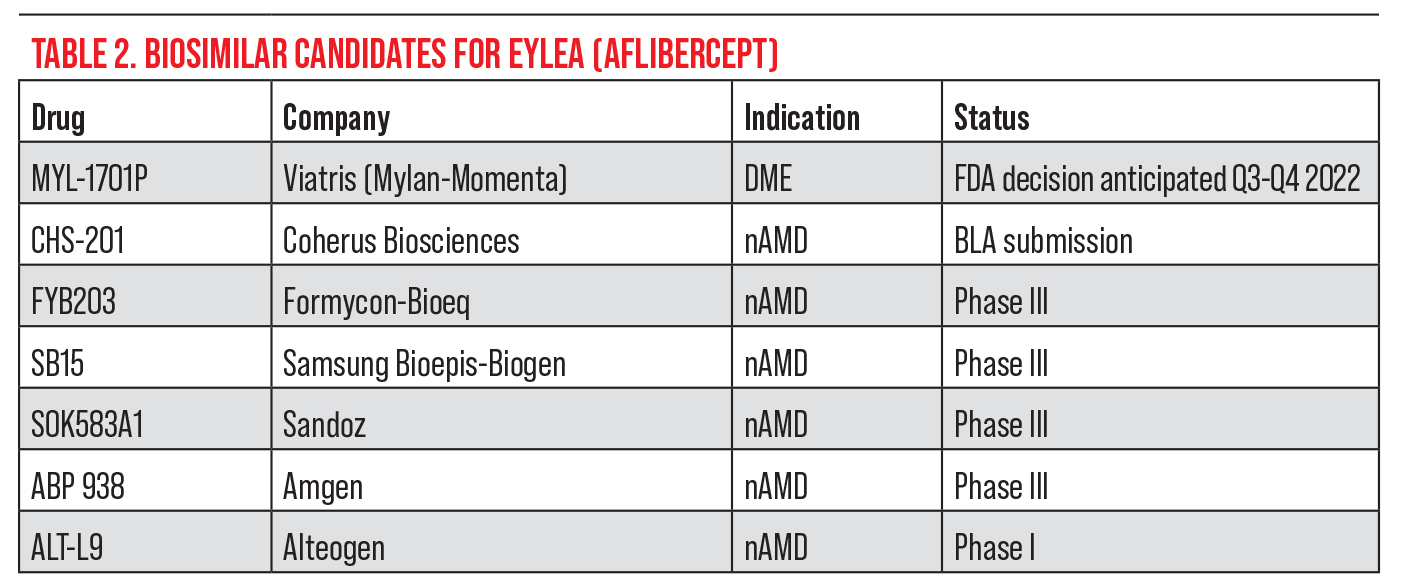

• Byooviz. Biosimilars are biological products that are highly similar to a reference product and have no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity and potency.6 In the United States, biosimilar uptake remains slow. Though there are 35 approved biosimilars to 11 reference drugs, only 21 of these are on the market.7 It’s estimated that biosimilars could save more than $133 billion by 2024 if uptake increases. Experts say that biosimilars will create cost-savings by launching at a discounted price, which will in turn cause the reference biologic product’s price to go down in response to competition (see Table 1).

Byooviz (ranibizumab-nuna, Samsung Bioepis/Biogen) is the first biosimilar in ophthalmology, referencing Lucentis. The drug launched on July 1 in the United States after receiving FDA approval last year. It’s priced at $1,130 for a single-use 0.5-mg vial, or 40 percent lower than Lucentis.

Not all retina specialists are eager to adopt a biosimilar, however. “Biosimilars have a minimal role in my practice,” says Dr. Khanani, citing established anti-VEGF agents with long safety records. “Unless the payers [mandate step therapy] through biosimilars, I don’t see myself using biosimilars in my practice at this point.”

“It’ll be interesting to see how effective biosimilars really are, and how others will be priced and marketed in the future,” says Dr. Haddock. “I haven’t had any experience with biosimilars so far. The excitement is perhaps about the reduced price, but we have reservations about manufacturing changes, as even a slight one could have serious effects. We’ve seen this happen with other molecules where changing a little bit can have serious effects in the eye. I’m not overly excited about it.”

Dr. Brown, who worked with Samsung Bioepis on the biosimilar trials, says he’s not concerned about the manufacturing because “Samsung has a robust biosimilar program and factory in Korea.” The company’s portfolio currently contains five biosimilars in addition to ranibizumab, including those for etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, trastuzumab and bevacizumab.

Dr. Brown says Byooviz and future biosimilars will put more pressure on insurance companies to manage costs. Despite that, he points out, “We don’t know how much of an effect [on the market] it’s going to have because it’s a biosimilar of Lucentis, which has been out now for 15 years and has been supplanted, especially in DME, by Eylea. So there aren’t as many patients on Lucentis to switch over to Byooviz. Insurance companies could add a step edit, which would push more doctors to get comfortable with the biosimilar, but how excited are insurance companies going to be about putting a separate step edit between Avastin and Eylea or Vabysmo or even Lucentis? There’s certainly more cost-savings with $75 Avastin than $1,130 Byooviz.

“I think what will really make a difference in the biosimilar market is an aflibercept biosimilar to compete with Eylea, which is the current market leader,” he continues (see Table 2). “I think there will be a cautious entry into the biosimilar market, but I’m hopeful we won’t see troubles like with brolucizumab, and we’ll certainly be diligent as we would be with any new agent.

“One concern is that Lucentis is currently marketed in two doses, 0.5 mg for AMD and 0.3 mg for DME, but Byooviz is only approved for AMD,” Dr. Brown says. “In some parts of the country, AMD is a large part of the market, consisting mainly of older white folks. Here in south Texas, about half of our patients have diabetes, and Byooviz doesn’t have that indication, so that will hurt its uptake.”

The American Academy of Ophthalmology supports the use of biosimilars, specifically those approved for ophthalmic indications. They say choice of treatment should remain between the treating ophthalmologist and their patient; they don’t support step therapy programs.7

“This is an exciting time for treating nAMD,” Dr. Haddock says. “We have several new treatments, and biosimilars are being introduced. There’s a lot to consider when deciding which treatments to use, but fortunately for patients, our latest treatments last longer, reduce the number of injections, reduce overall risk and maintain vision. I look forward to a future of individualized treatment driven by multiple treatment options.”

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Brown is a consultant for Samsung, Regeneron, Genentech and Novartis. Dr. Khanani is a consultant for Regeneron, Genentech and Novartis. Drs. Haddock, Han and Chhablani have no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Li E, Donati S, et al. Treatment regimens for administration of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020;5:CD012208.

2. Khanani AM, et al. Safety outcomes of brolucizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Results from the IRIS Registry and Komodo Healthcare Map. JAMA Ophthalmol 2022;120:1:20-28.

3. Zarbin M, Tsuboi M, Hill LF, et al. Simulating an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor switch in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2019;126:849-855.

4. Ferris FL 3rd, et al. Evaluating effects of switching anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs for age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:2:145-149.

5. Tuerksever C, et al. Hypothetical switch of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: An ARIES post hoc analysis. Ophthalmol Ther. [Epub January 23, 2022].

6. FDA. Biosimilarity and Interchangeabiliy: Additional draft Q&As on biosimilar development and the BPCI Act. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/143847/download.

7. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Biosimilars Forum: Unlocking the potential of biosimilars for treating retinal vascular disease, June 10, 2022. Webinar.

8. Sood S, et al. Cost of ranibizumab port delivery system vs intravitreal injections for patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmology. [Epub June 16, 2022].