Even after decades of clinical research and practical experience with glaucoma, the unfortunate reality is that many individuals still progress to advanced disease, despite our best efforts. If you’re a glaucoma specialist, anywhere from 25 to 50 percent of your patients probably would meet a definition of advanced glaucoma. Given this reality, you might expect the monitoring and treatment of advanced glaucoma to be a subject of much research and discussion. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case.

In fact, there’s very little literature addressing this aspect of the disease. Most glaucoma research has focused on detecting and treating early glaucoma—for example, developing new structural approaches to detection using technologies like spectral domain optical coherence tomography, or attempting to detect loss of function earlier with alternative technologies such as blue-on-yellow perimetry. Despite these technologies’ potential advantages as tools for early glaucoma detection, they have very limited usefulness when it comes to monitoring advanced glaucoma. Once tissue damage becomes severe, they’re unable to differentiate further loss in a meaningful way; they can’t tell us if the patient is getting worse. In fact, to date, no one has developed tools that are specifically designed to monitor patients with advanced disease.

Detecting Progression

Despite the difficulty of monitoring patients with late-stage disease, there’s no question that it’s important to do so. In fact, as vision is lost, one might argue that protecting the remaining vision is more important than ever.

A few years ago we conducted a study that we never published; we referred to it as the GON 10.9 project—short for glaucomatous optic neuropathy patients with 0.9 cups, followed for 10 years. All of those patients initially would have been regarded as severe but functional; they could read, walk in the door on their own and drive. But even though most of them were being managed by glaucoma specialists, and despite the fact that most of them had pressures in the mid-teens, 20 percent were legally blind by the end of the 10-year period. Clearly, our current approach isn’t sufficient to help these patients as much as we’d like.

|

The one structural technology that may be able to help in this situation is Fourier domain OCT, which can measure the ganglion cell complex. Depending on which study you read, anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of all retinal ganglion cells are congregated in the macular region. Because FD-OCT has a higher density array of A-scans and B-scans, it can segment the ganglion cell complex into its component parts—the nerve fiber layer, the axons, the ganglion cell layer, the cell bodies and the inner plexiform layer dendrites. Being able to assess this level of detail in this key part of the retina may allow us to follow advanced glaucoma more carefully and objectively.

Among the functional tests, standard perimetry becomes relatively useless for monitoring change once tissue damage is extensive. In today’s Humphrey visual field 30-2 or 24-2 tests, the patient has no sense of how he’s doing, and when the patient has advanced glaucoma, most of the “questions” go unanswered because the patient can’t see most of the stimuli. So the patient just sits there holding the buzzer, struggling to maintain concentration. (An alternative that can be helpful in a small proportion of patients with advanced glaucoma is the Humphrey visual field 10-2 test. This tests a smaller area of the central visual field, which can keep some patients more alert. Using a brighter stimulus can also help in some patients.)

One perimetry test that might be able to detect fine degrees of damage at this stage is the Goldmann visual field test. Because the Goldmann test is conducted by a technician, the patient stays focused and interested. Furthermore, with a live person running the test, it’s easier to focus in on the vision the patient has left. Goldmann perimetry is the kind of test that changes the signal-to-noise ratio in a way that theoretically could allow you to detect functional change in patients with advanced glaucoma. And there’s no question that it’s less frustrating for the patient.

The drawbacks, however, are obvious. Among other things, the Goldmann test requires an experienced technician, takes significantly longer than Humphrey perimetry and requires larger equipment, which most practices no longer own. So despite its potential advantages in this situation, the practical realities make it untenable as a monitoring method.

Given the limits of current technology, it would be a mistake to overlook what is likely the most useful functional test of all: the “How are you doing?” test. If a patient has clear media but she’s telling you that she’s getting worse and having more difficulty performing activities of daily living, that is a serious complaint that needs to be taken into consideration. In all likelihood, it means the disease is progressing, and you may need to consider altering your treatment protocol.

Managing Progression

What should we do if the evidence suggests that a patient with advanced glaucoma is still progressing? Unfortunately, the existing clinical evidence isn’t much help; there’s not a single study that addresses the question of whether lowering IOP even further is appropriate for these patients. We can always dodge the question by saying there’s no evidence either way, but the bottom line is, we see patients like this every day. So we each need to formulate some kind of an opinion about this, because these patients need our help.

I would come down on the side that these patients need a lower pressure. In my experience, some of these patients will progress anyway, but a significant percentage of them actually can be stabilized. So there’s a good chance you’ll help the patient if you can achieve an even lower IOP—for example, somewhere between 7 and 10 mmHg.

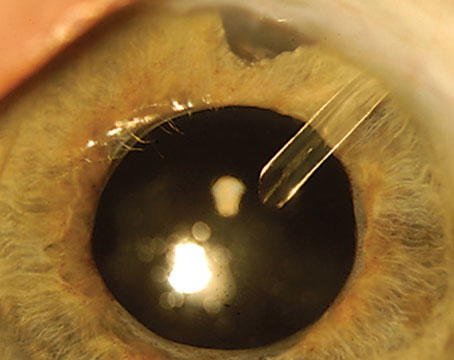

The question is, how aggressive should we be in this situation? I think that’s an individual choice, based on the patient’s willingness to take risk, her age, how easy it would be to achieve a lower pressure, and other factors involving ocular anatomy. At this point, of course, drops are of little use. Neither medications nor laser normally produce the kinds of pressures that are necessary to stabilize an advanced glaucoma patient. So, surgery is likely to be the remaining choice. However, in some situations you have to back off. The patient may be a very high myope or a monocular patient; a trabeculectomy with mitomycin-C could put such a patient at high risk for hypotony maculopathy, potentially causing visual disability. It’s a decision that has to be made on a case-by-case basis. But if the opportunity is there, I believe inaction may be a riskier choice in terms of the patient’s visual prognosis.

|

|

|

|

| Advanced age is not a reason to be less vigilant about a patient's disease. This 100-year old patient is in excellent health except for advanced POAG. Note that the visual field reliability parameters are in the acceptable range.

| |

General Strategies

Here are some specific things we can do to improve the chances that our advanced-glaucoma patients will retain vision:

• Stage the disease. I think it’s important to know which patients in your practice have early, moderate and advanced glaucoma. This doesn’t require a terribly sophisticated grading scheme that takes a long time to figure out, only a simple staging scheme. But it’s worth having because it helps you determine how you’re going to monitor and manage different patients. (You would certainly manage a 90-year-old with early disease differently than a 48-year-old with advanced disease.)

A simplified system for staging patients based on structure would probably be unworkable; cup:disc ratio, for example, varies considerably in a normal population because disc size varies in the normal population. So, you can have a rather large cup without any disease whatsoever. But a staging system can be based on the patient’s mean deviation score from a Humphrey visual field. (Elizabeth Hodapp, MD, Richard K. Parrish, MD, and Douglas R. Anderson, MD, at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute have devised such a scheme.) The mean deviation can be confounded by cataract, but for patients with relatively clear media, this can work well. Those with a mean deviation between 0 and -6 decibels could be regarded as having early disease; those with a mean deviation between -6 and -12 could be regarded as moderate; and those with a mean deviation worse than -12 could be regarded as advanced. By the latter stage, the patient’s retinal sensitivity across his entire field is more than one log unit reduced compared to age-matched controls.

• See the patient more frequently. When the pressure is already at 12 mmHg, it’s tempting to think you’ve done all you can do and just tell the patient to return in six months. But if a patient with advanced disease is failing the “how are you doing” test, it’s possible that you’re missing a pressure of 21 or 22 between visits. If you see the patient more often, you may uncover evidence that you really do need to intervene further. For these patients, my default follow-up is every three to four months.

• Consider referring the patient. If you’re a general ophthalmologist, and one of your glaucoma patients with advanced disease seems to be worsening, it might be useful to get at least one-time feedback from a glaucoma specialist. Of course, even glaucoma specialists don’t have a magic wand that can cure these patients—or even necessarily prevent further progression. But in some cases, a glaucoma specialist may be able to provide some insights and treatment suggestions that will help preserve vision.

• Use the “How are you doing?” test. This is an easy and often very effective way to monitor an advanced glaucoma patient’s condition. Given the shortage of alternatives, it’s a probing question we should ask every one of our late-stage patients.

• Reset your target pressure. Although the usefulness of this strategy in advanced disease has not yet been demonstrated via clinical trials, we know it’s effective in early disease. With so few tools available to preserve vision in these patients, it makes sense to consider lowering pressure further, as long as it’s feasible to do so given the individual’s condition.

• Don’t be fooled by age. Despite our best intentions, it’s easy to be influenced by appearances. For one thing, many advanced glaucoma patients are young. Younger patients often find ways to compensate to some degree for loss of vision, and their age may contribute to the impression that their problem is not as serious. They may come in sounding lively and vivacious; we don’t get the sense that they’re disabled in any way. But maybe we’re not talking to them enough and finding out what things disappoint and frustrate them as a result of being disabled. This form of age bias, combined with our desire to see our patients as doing well under our care, may cause us to underestimate the extent of their problem.

At the same time, it’s possible to prematurely throw up our hands when an older patient is in trouble. When I started practice in 1992, I thought that when patients reached the age of 90 there was little point in continuing with visual fields; I thought at that point, any vision that remained was a bonus. What a terrible attitude! Today I have many patients hitting the 90- and 100-year marks in good health; glaucoma is the only threat to their wellbeing. One 100-year-old patient always comes to my clinic wearing a suit and tie. He always says, “God bless you and your family! I wish you well!” He’s totally with it. He has advanced glaucoma, but he doesn’t look like he’s going to slow down any time soon. Patients like him are just as much in need of our help as younger patients with glaucoma.

Getting Back on the Case

Managing and treating patients with advanced glaucoma is the elephant in the room, despite the fact that it’s seldom discussed. Because our resources for managing these patients are limited, it’s easy to avoid spending a lot of time identifying them and figuring out how to help them. That’s a mistake we should avoid making.

As I noted earlier, there’s a significant lack of data regarding these patients. Given that situation, I’d encourage ophthalmologists to consider sharing whatever data they have via publication. It’s not the “sexiest” topic, but it’s one on which we really need input. Even global data on how advanced glaucoma patients in a practice are doing could help us further our efforts to keep these patients from losing more vision. It’s a subject we need to give a much higher priority.

Dr. Pasquale is director of the glaucoma service and associate director of telemedicine at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; clinical assistant scientist at Schepens Eye Research Institute; and associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School.