In 1905, American philosopher George Santayana stated that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” For blepharitis management, however, both remembering the past and repeating it are necessities. Learning from and improving upon prior treatments based on a current medical understanding of the disease allows for implementation of new treatment regimens and alterations of existing classification systems. Though the last decade has produced significant progress in the area of blepharitis, a definitive treatment, diagnosis and definition have remained works in progress.

The Basics of Blepharitis

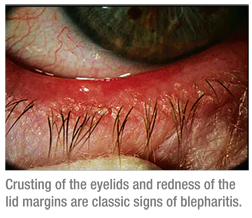

Characterized by long-term, repeated episodes of acute flare-ups, it’s commonly accepted that blepharitis is an inflammation of the eyelid margin, which involves the lid and its dermis, eyelashes, tarsal conjunctiva, mucocutaneous junction and the meibomian glands. Signs and symptoms of blepharitis include swelling, thickening, scaling and/or crusting of the eyelids, redness of the lid margins, bulbar and palpebral hyperemia, gritty eyes and itchy eyelids. However, when one takes a closer look at the disease, a simple definition doesn’t suffice.

Scholars have long expressed frustration with the disease’s pathogenesis; ophthalmologist Phillips Thygeson noted in 1946 that “textbook discussions of blepharitis have long seemed to me to be regrettably inadequate with respect to both etiology and therapy.”1

Even though blepharitis is one of the most frequently observed conditions, with some form of blepharitis present in 15 to 25 percent of the population,2 it’s also one of the most frequently mistreated due to a plethora of possible etiologies and symptoms that overlap with other ocular surface diseases. For example, a recent survey concluded that 34 million adults experienced at least one of the three symptoms most commonly associated with blepharitis in the past year, yet only 4.5 million people have received treatment for their blepharitis.3

A number of possible causes for blepharitis have emerged, including bacterial components such as Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Propionibacterium acnes and Corynebacteria sp.;4 rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, microscopic mites (demodex folliculorum), lipophilic yeast found in cutaneous flora such as Pityrosporum ovale; contact allergy and androgen deficiency. Even drug therapies like isotretinoin have been named as likely sources. Many studies have been conducted to identify the nature of preoperative normal conjunctival flora; they have shown the existence of both pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria, with S. aureus being the most frequent pathogen recovered.5 Even for nonpathogenic bacteria like S. epidermidis, increased colony density leading to quorum sensing can cause these bacteria to undergo a genetic shift and produce inflammatory mediators. Out of these etiologies, the most common medical opinion is that one-third of blepharitis is caused by a staphylococcal infection, one-third by seborrheic dermatitis and the rest by a combination of both forms. While many of these pathophysiologies have been identified, a more meaningful analysis of etiologies should be explored. Accurately diagnosing individual cases of blepharitis can be rather complicated, yet is essential for proper treatment. There are a substantial number of Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments of ocular diseases, such as allergic conjunctivitis, but there is still no approved drug indicated for the treatment of blepharitis. The dearth of definitive treatments combined with the physicians’ need for one creates a sense of urgency in finding an appropriate treatment.

The Domino Effect

The differential diagnosis of blepharitis can be difficult. In addition to a multitude of possible etiologies, blepharitis signs such as redness and swelling are often associated with other ocular surface diseases, which can obscure the path to an effective treatment. Ocular surface diseases can also be circular, as the presence of one condition can cause another to develop. Blepharitis can include an inflammation of the conjunctival tissue (blepharoconjunctivitis) and/or the cornea (blepharokeratoconjunctivitis), or both. Blepharitis, therefore, is an important part of the differential diagnosis of associated ocular surface diseases.

|

There’s also a significant connection between blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. In 1977, it was proposed that an unstable tear film was the result of an abnormal meibomian gland condition, and the following year, an analysis of the meibomian gland lipids from normal subjects suggested that there were large lipid variations among individuals.9,10 These studies set the foundation for researchers to more closely inspect the relationship between tear-film production and meibomian gland dysfunction. Meibomian gland dysfunction directly impacts the tear film, facilitating the loss of the lipid barrier, which, in turn, accelerates evaporative dry eye.2 Meibomian gland lipids are expelled as meibum onto the ocular surface by a gland orifice located at the mucocutaneous junction of the lid margin.11 Once infected or irritated, undesirable secretions can be brought to the ocular surface, as well. For example, patients with meibomian seborrhea, who often present with severe burning symptoms, have an increase in oleic acid in their meibum.12 Researchers also analyzed the human meibomian gland using in vivo confocal microscopy to show that a thickening of the eyelid is caused by a hyperkeratinization of the ductal epithelium and a shedding of the keratinized material into the glandular ducts, which can lead to orifice obstruction and inflammation.13

Devising a Treatment

In an effort to accurately diagnose, treat, and promote effective methods to halt the progression of the disease and prevent blepharitis from recurring, a retrospective glance at its history can help. The origins of blepharitis treatment are lined with milestones of progress, though not all are consistent with current medical understanding. For instance, a 1908 Optical Review advertisement recommended the use of Great German Eye Water—an antiseptic that advertised itself as “the most effective preparation ever compounded for blepharitis,” and was meant for “weak or inflamed eyes, granular or scaly eyelids, or any inflammation caused by overwork or injury to the eyes.”14 In 1942, a study concluded that based on a review of the anatomy and physiology of the meibomian glands, staphylococci residing in the meibomian glands play a predominant role in the recurrence of conjunctivitis.3

In 1946, Dr. Thygeson conducted extensive blepharitis research and set the trajectory for future blepharitis therapies. He described blepharitis as “a chronic inflammation of the lid border,” and split it into two broad categories: the squamous (characterized by hyperemia of the lid border with dry or greasy scales) and the ulcerative (characterized by the development of small pustules involving the follicles of the cilia and leading to the formation of small ulcers).15 Dr. Thygeson further categorized blepharitis into three main types: staphylococcic blepharitis; seborrheic blepharitis and mixed seborrheic and staphylococcic blepharitis.15 Even though Dr. Thygeson found lid hygiene methods to be somewhat effective, he observed that penicillin was the more successful treatment for staphylococcic blepharitis, noting that “infection of the meibomian glands is the greatest single factor that must be overcome.”15 His combination therapy of antibiotics and lid hygiene became the standard for blepharitis treatment for many decades.

|

Though there were treatments to alleviate symptoms, Dr. McCulley, among others, came to the conclusion that there might not be a cure for blepharitis. It was suggested that aside from staphylococcal blepharitis, there was no cure for blepharitis and that only a management of the condition could be achieved.3 As time progressed, the thought process remained the same: In 1995, two researchers declared blepharitis a “diagnostic and therapeutic enigma.”17 They agreed with the estimation that there was no long-term cure for blepharitis, only relief with a combination of lid hygiene measures and topical antibiotics, and went even further to say that staphylococcal blepharitis was incurable as well.17 Their estimation stemmed from the hypothesis that individuals with blepharitis were likely to be highly susceptible to the causative organism that would lead to eventual chronic recurrences of the condition.17

A Name Change

With research at a standstill and a number of classification systems circulating upon the blepharitis stage, conventional wisdom thought it would be beneficial to construct more comprehensive classification systems in the hope of initiating more efficient treatments. In parallel, a similar standstill was reached in the 1990s concerning dry-eye disease. In response to the stagnation of new developments, the National Eye Institute and members of the ophthalmic industry sponsored a meeting of clinicians and researchers that created a universally accepted definition and classification of dry-eye disease that formed the basis of more than a decade of research.18 Much like the change in course for dry-eye research, the past decade of research has driven the creation of a new standard definition of blepharitis and a renewed understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the disease.

In 2004, William Mathers, MD and Dongseok Choi, PhD, used cluster analysis to create a classification tree that demonstrated that blepharitis and dry eye can be differentiated with objective physiologic tests into clinically relevant groups having common characteristics.19 Their classification system also recognized the central role of meibomian gland dysfunction in blepharitis and demonstrated the diverse characteristics of the normal population.19 The current classification system for blepharitis, however, was developed in 2006 when a research group developed standardized, photo-validated scales for blepharitis and meibomitis based on anatomical classifications. These anatomical classifications include assessing the lash follicles, dermis, eyelid, vascularity, mucocutaneous junction, meibomian gland orifices and tarsal conjunctiva. Digital images were reviewed by a panel of clinicians and were arranged from least severe to most severe; representative images were then selected to generate a scale of 0 to 3 or 0 to 4 (normal to severe).

These scales have been used in multiple studies conducted by our research group at Ora Inc., for the treatment of blepharitis,20-22 and have been established as the disease’s standard classification system. One such study supported by Allergan in collaboration with Schepens Eye Research Institute compared testosterone 0.03% ophthalmic with a placebo and showed that testosterone was effective in relieving symptoms consistent with blepharitis, as the meibomian glands are regulated by androgens and promote the formation of the tear film’s lipid layer.22-24 The work conducted by co-author Aron Shapiro and Japan’s Kazuo Tsubota, MD, has shaped our current understanding of blepharitis and helped provide both clarity and structure for evaluating new therapies.

Where Things Stand

With a validated classification system in place, our knowledge of blepharitis treatment has progressed. The use of corticosteroid therapy in combination with antibiotic treatment has become the standard of care to alleviate patients’ blepharitis symptoms. The steroid is used to treat the inflammatory symptoms, while the antibiotic prevents and treats the secondary infection. Safer dosing of steroids used in short pulse therapies has vastly changed the landscape for blepharitis treatment.

Azithromycin has typically been the antibiotic of choice to treat bacterial blepharitis in the modern age, though the recently approved tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension Tobradex ST has shown excellent efficacy in ridding the eye of blepharitis symptoms.21 Tobradex ST is a change in formulation from the original Tobradex, with a decrease in the amount of steroid (from 0.1% to 0.05%) and the addition of an inactive agent (xanthan gum), to stabilize the combination and increase contact time. In a multicenter, randomized, investigator-masked, and active-controlled, 15-day study sponsored by Alcon, Tobradex ST quickly controlled the signs and symptoms of blepharitis, including lid margin redness, palpebral conjunctival redness, ocular discharge, itchy eyelids and gritty eyes; and researchers observed a statistically significant lower mean global score in subjects treated with ST compared to subjects treated with azithromycin at day eight.21

Though often frustrating, blepharitis research has made significant strides and is continuing to do so. Modifying treatments of the past, creating new ways to classify and clarify the disease, and using new medical discoveries has allowed blepharitis researchers to push forward in finding innovative approaches to blepharitis treatment, without forgetting the novel developments that put them on the right path in the first place. Learning from the past will allow clinicians and patients to move into a future where an FDA-approved drug for the effective treatment of blepharitis is on the horizon.

Dr. Abelson, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and senior clinical scientist at Schepens Eye Research Institute, consults in ophthalmic pharmaceuticals. Mr. Shapiro is director of anti-infectives and anti-inflammatories, and Ms. Tobey is a medical writer, at Ora Inc., in Andover.

1. Thygeson P. Etiology and treatment of blepharitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1946;36:445-477.

2. Donnenfeld ED, McDonald MB, O’Brien TP, Solomon KD. New considerations in the treatment of anterior and posterior blepharitis. A continuing medical education supplement. Refractive Eyecare 2008;12:4.

3. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: A survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf 2009;7:S1-S14.

4. Groden LR, Murphy B, Rodnite J, Genvert GI. Lid flora in blepharitis. Cornea 1991;10:1:50-53.

5. Abelson MB, Allansmith MR. Normal conjunctival wound edge flora of patients undergoing uncomplicated cataract extraction. Am J Ophthalmol 1973;76:4:561-565.

6. Mathers WD. Ocular evaporation in meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye. Ophthalmology 1993;100:3:347-351.

7. Pflugfelder SC, Solomon A, Stern ME. The diagnosis and management of dry eye: A twenty-five-year review. Cornea 2000;19:5:644-649.

8. Zoukhri D. Effect of inflammation on lacrimal gland function. Exp Eye Res 2006;82:5:885-898.

9. McCulley JP, Sciallis GF. Meibomian keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1977;84:6:788-793.

10. Tiffany JM. Individual variations in human meibomian lipid composition. Exp Eye Res 1978;27:3:289-300.

11. McCulley JP, Shine WE. Meibomian gland function and the tear lipid layer. Ocul Surf 2003;1:3:97-106.

12. McCulley JP, Shine WE. Eyelid disorders: The meibomian gland, blepharitis, and contact lenses. Eye Contact Lens 2003;29:S93-95; discussion S115-118, S192-114.

13. Ibrahim OM, Matsumoto Y, Dogru M, et al. The efficacy, sensitivity, and specificity of in vivo laser confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of meibomian gland dysfunction. Ophthalmology 2010;117:4:665-672.

14. Advertisement. The original and only great german eye water. The Optical Review 1908;2:2:15.

15. McCulley JP, Shine WE. Changing concepts in the diagnosis and management of blepharitis. Cornea 2000;19:5:650-658.

16. McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology 1982;89:10:1173-1180.

17. Smith RE, Flowers CW, Jr. Chronic blepharitis: A review. CLAO J 1995;21:3:200-207.

18. Lemp MA. Report of the National Eye Institute/Industry workshop on Clinical Trials in Dry Eyes. Clao J 1995;21:4:221-232.

19. Mathers WD, Choi D. Cluster analysis of patients with ocular surface disease, blepharitis, and dry eye. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:11:1700-1704.

20. Comparative Study of AzaSite Plus Compared to AzaSite Alone and Dexamethasone Alone to Treat Subjects with Blepharoconjunctivitis.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00754949?term=azasite+dexamethasone&rank=1. Accessed October 5, 2010.

21. Torkildsen GL, Cockrum P, Meier E, Hammonds WM, Silverstein B, Silverstein S. Evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety of tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension 0.3%/0.05% compared to azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% in the treatment of moderate to severe acute blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin;27:1:171-8.

22. A single-center, double-masked, randomized, vehicle controlled study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of testosterone 0.03% ophthalmic solution compared to vehicle for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00755183?term=single-center+testosterone&rank=1. Accessed October 5, 2010.

23. Androgen Tear: Ocular Surface Disease.

http://www.allergan.com/research_and_development/pipeline.htm#. Accessed January 19, 2011.

24. Krenzer KL, Dana MR, Ullman MD, et al. Effect of androgen deficiency on the human meibomian gland and ocular surface. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:12:4874-4882.